The Commercialization of Higher Education: A Global Perspective

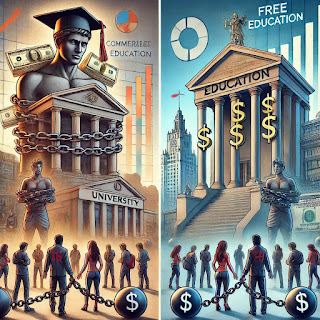

In the mid-1960s, 13 million students were enrolled in higher education globally. By 2015, this number had surged to 200 million, and projections suggest it will reach 400 million in less than 15 years. This exponential growth in demand for higher education has led to a corresponding increase in tuition fees worldwide, raising critical questions about the accessibility and affordability of education. This article explores the transformation of higher education into a commercialized sector, examining the implications of rising tuition fees, the influence of economic theories on educational policies, and the contrasting approaches of different countries.

As the demand for higher education grows, so do tuition fees. In many parts of the world, the cost of education has reached staggering heights, burdening students with significant debt. For example, in the United Kingdom, the introduction of tuition fees in 1998 marked the end of free higher education. Initially set at £1,000 per year, these fees have steadily increased, reaching £9,000 per year by 2010. This shift was driven by the need to fund universities amidst growing student numbers and declining public funding.

The United States presents an even starker picture. Higher education institutions, particularly private ones, have long charged high tuition fees. Today, the student debt crisis has reached a critical point, with total student debt amounting to over $1.3 trillion. This burden has profound implications for graduates, who face decades of repayment, often stifling their economic prospects and contributing to broader societal inequalities.

The shift towards high tuition fees is underpinned by economic theories that emerged in the 1960s and gained prominence in the late 1990s. One such theory is the concept of human capital, which views education as an investment that enhances individual productivity and, by extension, economic growth. This perspective has been instrumental in shaping policies that treat education as a commodity rather than a public good.

In Europe, the influence of this economic thinking became evident in the late 1990s when countries sought to reform their higher education systems to boost competitiveness. England led the way by introducing tuition fees and later increasing them, aligning with the broader neoliberal agenda of applying private sector management models to public services.

The commercialization of higher education is also driven by global competition. Universities are increasingly seen as strategic assets in the global knowledge economy, with countries vying to attract international students and top researchers. This competition has led to the proliferation of university rankings, which prioritize metrics such as research output and international collaboration.

China's rise as a major player in higher education exemplifies this trend. With millions of students and significant investment in research and development, China has rapidly expanded its higher education sector. The Shanghai ranking, developed by Jiaotong University, has become a widely followed benchmark, influencing university policies worldwide.

The commercialization of higher education has profound implications for students, universities, and society at large. Students face escalating costs and mounting debt, which can limit their career choices and financial stability. In the United States, the proliferation of for-profit colleges has further exacerbated these issues, often targeting vulnerable populations with promises of upward mobility that fail to materialize.

In the UK, the high tuition fees have led to a shift in university priorities. Institutions increasingly operate like businesses, with vice chancellors assuming the role of chief executives. This market-oriented approach can undermine the quality of education and the public good, as universities focus more on revenue generation than on their educational mission.

While many countries have embraced the commercialization of higher education, others offer alternative models that prioritize accessibility and equity. Northern European countries like Denmark and Sweden and scotland provide free education and grants to students, fostering an environment where higher education is seen as a public good. These countries emphasize the student experience and the development of critical thinking, rather than treating education as a commodity.

Germany, after briefly experimenting with tuition fees, has returned to a system of free higher education. This decision reflects a broader societal commitment to ensuring that education remains accessible to all, regardless of economic background.

The commercialization of higher education is a global phenomenon with far-reaching implications. As tuition fees continue to rise and education becomes increasingly commodified, students around the world are grappling with the financial burdens and societal consequences. While some countries have fully embraced this market-oriented approach, others offer alternative models that prioritize equity and accessibility.

The future of higher education depends on our collective willingness to reimagine its role in society. We must decide whether we want an education system that serves the economy or one that serves humanity. By critically examining the current trajectory and exploring alternative models, we can work towards a more equitable and just higher education system for future generations.

Comments

Post a Comment